Repository | References | Zotero | BibTeX

A few years ago ago I was lucky enough to have some time to tinker with high-temperature ceramics. Very little of value was determined, primarily just empirical nonsense; I have not managed to figure out a consistent protocol for high-alumina parts. I figured I would quickly post the most useful fact in this document for the time being.

I am certain that nothing here is even slightly novel!

Many of my friends in the Vacuum Hackers discord and twitter (among others) have very interesting projects involving ceramic blends, and you should probably talk to them instead!

It’s relatively easy to get to 800 C or so with standard heating elements, microwave susceptors, or gas torches, sufficient for some low-fired >30% kaolin ceramic blends. With care in heating element support, termination, and insulation, commercial “high-fire” ceramics kilns can usually reach about 1300 C.

However, a very useful class of techniques practically demand a minimum of about 1400 C, including the most common high-purity oxide ceramics like Al2O3, MgO and AlN, even if sinter-point-depressing additives are used (see awesome data from Cutler et al. (1957) and Luks (1942)). I believe this can be partly attributed to a change in regime from “liquid-phase” to diffusion-like “vapor-phase” sintering processes ((“Sintering” n.d.)).

Furnaces that can reach such temperatures are usually quite expensive. Small zirconia sintering kilns are available, ostensibly for dental work, usually using MoSi2 heating elements, but these usually cost over $1500. There are a few sources of surplus high-temperature elements.

Acetylene torches do not appear to offer the required control over temperature ramp rate and produce strong thermal gradients that crack the green during burnout. Carbon-arc furnaces are pretty popular now but probably suffer from the same issues.

Some alternative techniques can often be used in specific circumstances, such as field-assisted sintering (Guillon et al. (2014), thanks (???)). However, a general-purpose desktop furnace for small parts seemed like a pretty useful piece of equipment.

More critically, if a vacuum furnace is desired, standard Nichrome or Kanthal heater wire degrades very rapidly. See, for instance, this striking quote from Mazelsky et al. (1974) :

The next factor investigated was the suitability of Kanthal A-1 as heater material. Although this material is suitable for use to 1325 C in air, at least one reference does not recommend its use in vacuum at temperatures over 1000°C. This warning is founded in the rapid evaporation of a component (chromium?) from the alloy and verified by tests we performed on bare wires in ultra-high vacuum. Sample filaments burned out after two hours or less at a surface temperature of 1200°C.

If a suitably high vacuum or inert atmosphere is available, sufficiently pure graphite or W, Ta or Mo boats can be made into acceptable heating elements, but it takes some effort to work around the low resistance of these materials.

I recommend a CoorsTek 271N (equivalent to Emerson 767A-372) SiC HSI ($33 CAD pre-pandemic on Amazon) or equivalent with fiberglass wire insulation, Steatite C220 or Alumina body and nichrome wire. Beware elements with Teflon insulation. Both recrystallized SiC and SiN HSIs are available. The SiC elements are preferable due to the higher temperature resistance of SiC and a more rugged construction overall. SiN HSIs also often specify an 80v DC supply for reasons unknown.

SiC HSIs are mechanically delicate, but seem to tolerate ceramic spall and contamination relatively well.

Note that 220V elements seem to be quite rare: it appears to be hard to fabricate something with a sufficiently high resistance.

HSIs are apparently used because sparks do not provide the energy needed to ignite natural gas with perfect reliability over decades.

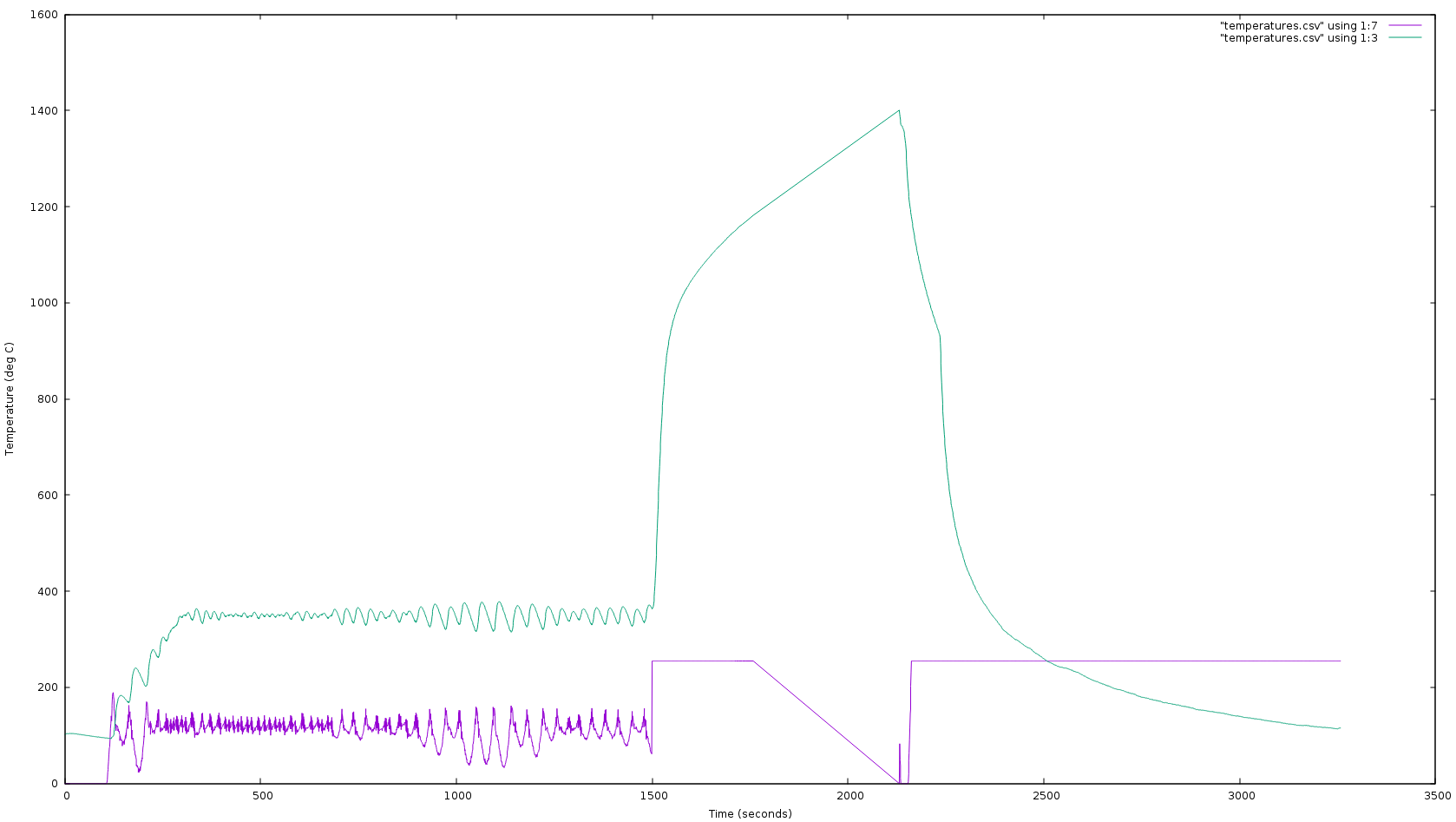

Getting above ~1500c involved increasing the 115V line voltage to about 135 V using a Variac. This does speed up element degradation a bit.

Of course, the element temperature must be higher than the furnace cavity; but they appeared to be sufficiently similar that I only report the temperature measured by thermocouple at the surface of the base.

I’ve consistently broken elements in idiotic ways before they burned out, so I have no data on lifespan; but you can probably expect on the order of a dozen hours at 1400 C in air.

Degradation occurs via a fascinating multi-step oxidation reaction described in detail by Raj and Terauds (2015) that evolves carbon monoxide and inflates large bubbles of SiO2 mixed with SiC (if I’m understanding correctly - unlikely, given poor chemistry prowess!):

Interestingly, a very similar “bubbling” failure mode was seen (Jacobson et al. (2008) Roth et al. (2010)) on the reinforced-carbon-carbon panels on the leading edges of the space shuttle, which were coated with SiO and SiC for oxidation protection.

Such a carbon-carbide “conversion coating” seems to be relatively easy to perform in a furnace such as this one; see (Blocher et al. (1957)). SiC heating elements are also used on the ALQ-144 thermal missile jammer, so it’s unlikely that my lab will be hit with a missile in the near future.

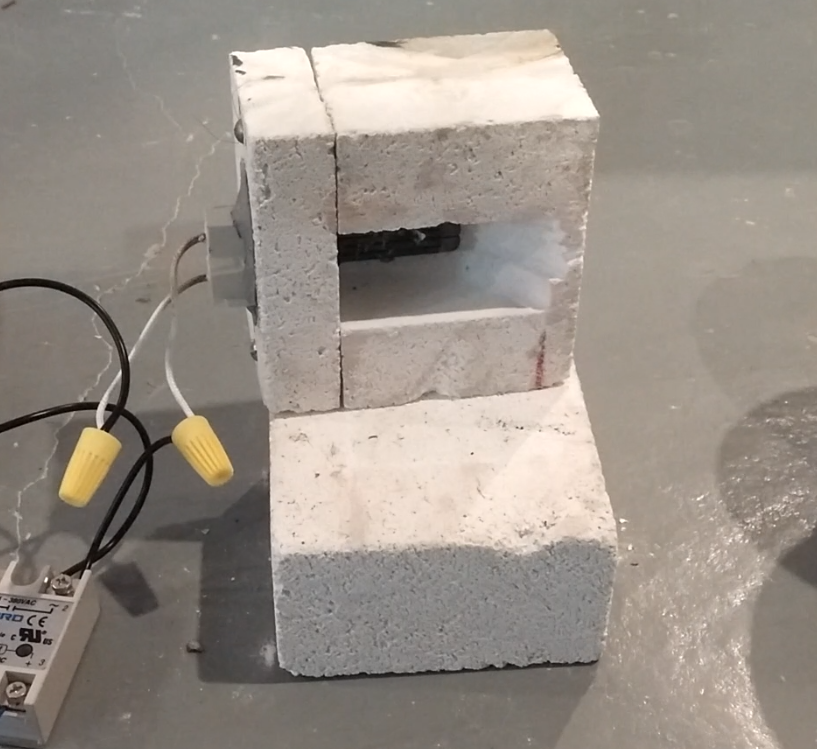

This kiln was built using a single Amaco 28035N 9" by 4-1/2" by 2-1/2" aluminosilicate firebrick ($15 pre-pandemic, Amazon) cut and pocketed using a wet tile saw (although a hacksaw would work fine); the element was then mounted with fire-cement (Imperial High-Temp Stove and Furnace Cement). The element was inserted through a slit in the firebrick to shield the terminals somewhat. Let cement dry overnight, then slowly raise temperature over course of ~30 minutes.

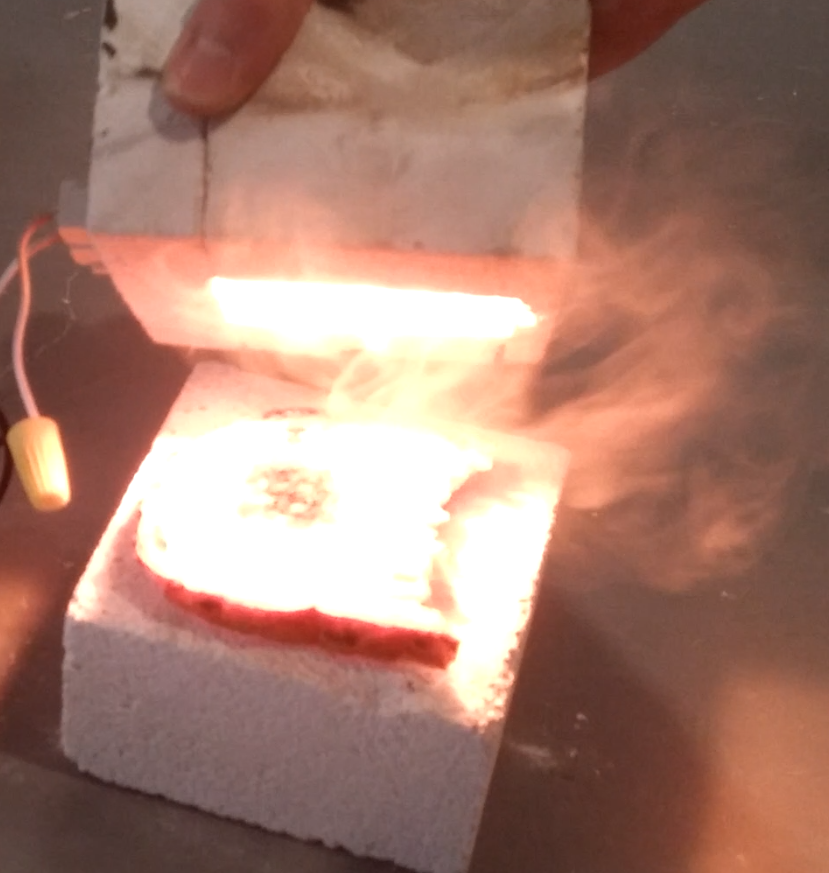

Fissures appear in the firebrick over the course of a few hours when running at 1500 C, but this doesn’t seem to be a serious issue.

The alumina-foam firebrick is quite delicate, and the end-cap to which the element was mounted later broke during handling. Mounting with threaded rods and large washers is recommended.

I really like this furnace. It typically reaches 1000 C in one minute, and 1400 C in the next five to ten, allowing for very rapid iterative testing (useful for my crude, blunderbuss style of R&D). It can also toast bread in 2.4 seconds. Some green binders (gelatine, for instance) are sensitive to temperature ramp rate. PVAc seemed unfazed by these crazy dT/dts.

A PID control system can be added with an SSR: P: 1, I: 1, D: 2 to 6 based on thermocouple response, and integral windup limits of -300, 300 seems to be an acceptable starting point.

Typical ratings range from a tepid 980 C at 102v to a positively balmy 1705 C at 132v (Inc (2017)). Expect consistent 3.7A draw over entire temperature range.

Standard thin K-type thermocouple wire can operate briefly at 1400 C; McMaster-Carr’s #3859K44 thermocouples survive a bit higher for a few minutes before being incinerated, though the high thermal mass leads to a ~200 C offset in this application (seen in the graph above).

Non-contact temperature measurement is more suitable, though all COTS bolometers begin to whimper at these temperatures.

The best option for temperature measurement is probably a disappearing-filament pyrometer. These are trivial to build.

If a Vis spectrometer is available, fitting the pleasant glow of the furnace to the Stefan-Boltzmann law can probably get you within a few hundred degrees.

A ratio pyrometer built from two photodiodes (or phototransistors, depending on your bias) with IR-cut and IR-pass filters may also work.

These techniques are complicated somewhat by alumina’s selective radiation: the spectral emissivity curve looks like someone put overcooked pasta into Matplotlib. Worse still, it varies with temperature by about half an order of magnitude. I’m disappointed to find that ‘spectral emissivity’ has nothing to do with ghosts.

Most insulating materials that can withstand such temperatures are expensive or difficult to work with. Because of the P ≈ T4 nature of the Stefan-Boltzmann law vs the approximately linear dependence of conduction, at such high temperatures radiative insulation is the primary concern. For this reason, many concentric shells of multi-layer insulation may suffice.

The advantage here is that the efficiency of MLI depends only weakly on the emissivity and conductivity of the insulation. For this reason, a stack of machined graphite may be sufficient.

20 oz vacuum-insulated wine tumblers seem to make excellent chambers for this purpose.

Suggest improvements on the GitHub issues page at https://github.com/0xDBFB7/ceramic, or hit me up @0xDBFB7 on Twitter!

❤

‘Gel-casting’ is a technique where a slurry of ceramic powder mixed with a low-viscosity monomer or polymer (prototypically acrylamide, but now various others Janney et al. (1998)) and crosslinker is injected into a mold, after which the crosslinker is triggered to form a solid green. This appears to be in vogue for ceramics production. Some advantages include very low binder percentages and correspondingly low green drying and firing shrinkage. Some effort was put into evaluating various gel-casting binders. (Chabert, Dunstan, and Franks (2008))

However, aqueous gel-casting has a notable drawback in that most common binders tend to entrain water, meaning that even thin cross sections take many hours to properly dry. A solution of PEG can apparently be used to accelerate this drying Barati, Kokabi, and Famili (2003) - I haven’t tried this. The required crosslinking activators and are also usually difficult to obtain for the hobbyist.

(Note that, confusingly, both PVAc, poly(vinyl acetate), and PVOH, poly(vinyl alcohol), are each often referred to as ‘PVA’, despite having completely different properties. Standard white glues are an emulsion of primarily PVAc and some PVOH).

Alginates are a pretty neat tunable binder; the molecules cross-link together whenever a Ca2+ or Mg2+ ion is present in solution, meaning that the viscosity and trigger can be tuned with various chelators or ionic salts Jia, Kanno, and Xie (2003).

Glutinous rice flour Wan et al. (2014) is the strongest readily-available gel-casting binder that I’m aware of.

I have, however, had much better results from so-called low-pressure injection molding with a 15% paraffin wax binder. Several suitable binders are discussed in Teter (1965). A plastic syringe suffices for injection.

Alumina can be readily brazed using titanium Beggs (1957). This requires only a titanium interface layer; several fancy intermetallics are formed and the titanium adheres strongly to the alumina. The entire process must take place in a high vacuum or exceptionally clean argon atmosphere, else inert titanium oxides and nitrides will form.

A soft copper or Kovar interface layer is often used to prevent the differing thermal coefficients from cracking the ceramic when the weld cools.

See Hammond, David, and Santella (1988) and Consultants (2009) for details.

Luks (1942) describe how Manganese Dioxide can be used to depress the sinter point of pure alumina to more reasonable temperatures, sometimes without the use of silica. An impure, graphite-contaminated MnO2 can be obtained from alkaline batteries; unfortunately, I have not yet been able to reproduce this effect.

The effects of sintering additives on the development of the crystalline structure are very interesting and counterintuitive (Brook (1976) Hine et al. (2009)). It would be interesting to see if these effects can be predicted with some accuracy by modern molecular dynamics procedures - something like DFT or Q ESPRESSO or HOOMD-Blue. I have done no research into this field - this is almost certainly already common practice.

A PVAc-bound alumina solution can be thinned considerably, and various objects can be dipped to form hard coatings. Attempts with graphite and aluminum have been successful; however, obtaining a uniform, tight-tolerance layer is somewhat difficult.

If such a layer is required, a variant of electrophoresis can be used; see Ferrari and Moreno (1997) and Lazic et al. (2004) for details. This technique is apparently often used to insulate indirectly heated cathodes.

Alumina can be found in two main allotropes: alpha-, and beta-. (and sapphire).

To my (surely flawed) understanding, the chief difference lies in the ionic conductivity, which allows for hermetic low-temperature anodic bonds to some materials using the esoteric Johnsen–Rahbek effect. See Dunn (1979).

If a thin gelatine binder is used in a sol-gel, the solution can be beaten like egg white into a low density insulating foam. I don’t know what this is useful for, but it’s neat.

Attempts at acetylene sintering.

Acetylene-sintered with 3% slip.

Perhaps it is useful to think about the test coupons that you use when optimizing processes. It seems like they should be as small, fast, and easy as possible while still reflecting the desired end product.

For instance, if you use an oversimplified test coupon, you might start overfitting your process to get good results on the coupon, rather than the final product you need. Don’t overthink it though.

Perhaps there is some information in the design-of-experiments literature on this topic that may be of some use.

For some reason, the tests that I ran were largely sequential; run one mixture, observe the effects, modify the mixture slightly, etc. Parallelizing and pipelining may have made this go faster.

Barati, Abolfazl, Mehrdad Kokabi, and Mohammad Hossein Navid Famili. 2003. “Drying of Gelcast Ceramic Parts via the Liquid Desiccant Method.” Journal of the European Ceramic Society 23 (13): 2265–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0955-2219(03)00045-1.

Beggs, J. 1957. “Sealing Metal and Ceramic Parts by Forming Reactive Alloys.” IRE Transactions on Component Parts 4 (1): 28–31. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCP.1957.1135908.

Blocher, J. M. Jr., C. J. Ish, D. P. Leiter, L. F. Plock, and I. E. Campbell. 1957. “CARBIDE COATINGS ON GRAPHITE.” BMI-1200, 4265033. https://doi.org/10.2172/4265033.

Brook, R. J. 1976. “Controlled Grain Growth.” In Treatise on Materials Science & Technology, 9:331–64. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-341809-8.50024-3.

Chabert, France, David E. Dunstan, and George V. Franks. 2008. “Cross-Linked Polyvinyl Alcohol as a Binder for Gelcasting and Green Machining.” Journal of the American Ceramic Society 91 (10): 3138–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02534.x.

Consultants, P. M. Roberts/Delphi Brazing. 2009. “Is It Possible to Braze Ceramics?”

Cutler, I. B., C. Bradshaw, C. J. Christensen, and E. P. Hyatt. 1957. “Sintering of Alumina at Temperatures of 1400 C. And Below.” Journal of the American Ceramic Society 40 (4): 134–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1957.tb12589.x.

Dunn, Bruce. 1979. “Field-Assisted Bonding of Beta-Alumina to Metals.” Journal of the American Ceramic Society 62 (11-12): 545–47. https://doi.org/10/bp8pbf.

Ferrari, B., and R. Moreno. 1997. “Electrophoretic Deposition of Aqueous Alumina Slips.” Journal of the European Ceramic Society 17 (4): 549–56. https://doi.org/10/d9rd5p.

Guillon, O., J. Gonzalez-Julian, B. Dargatz, T. Kessel, G. Schierning, J. RÃ?thel, and M. Herrmann. 2014. “Field-Assisted Sintering Technology/Spark Plasma Sintering: Mechanisms, Materials, and Technology Developments.” Advanced Engineering Materials 16 (7): 830–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/adem.201300409.

Hammond, J. P., S. A. David, and M. L. Santella. 1988. “Brazing Ceramic Oxides to Metals at Low Temperatures.” Welding J 67 (10): 227–32.

Hine, Nicholas DM, K. Frensch, W. M. C. Foulkes, M. W. Finnis, and A. H. Heuer. 2009. “Bulk Diffusion in Alumina: Solving the Corundum Conundrum.” https://casinoqmc.net/esdg_slides/hine030609.pdf.

Inc, CoorsTek. 2017. “High-Performance Heating Igniters.”

Jacobson, Nathan S., Don J. Roth, Richard W. Rauser, James D. Cawley, and Donald M. Curry. 2008. “Oxidation Through Coating Cracks of SiC-Protected Carbon/Carbon.” Surface and Coatings Technology 203 (3-4): 372–83. https://doi.org/10/b24jw5.

Janney, Mark A., Ogbemi O. Omatete, Claudia A. Walls, Stephen D. Nunn, Randy J. Ogle, and Gary Westmoreland. 1998. “Development of Low-Toxicity Gelcasting Systems.” Journal of the American Ceramic Society 81 (3): 581–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1151-2916.1998.tb02377.x.

Jia, Yu, Yoshinori Kanno, and Zhi-Peng Xie. 2003. “Fabrication of Alumina Green Body Through Gelcasting Process Using Alginate.” Materials Letters 57 (16-17): 2530–4. https://doi.org/10/bkf4fb.

Lazic, Marija, Kornelija Simovic, Vesna Miskovic-Stankovic, Predrag Jovanic, and Dusan Kicevic. 2004. “The Influence of the Deposition Parameters on the Porosity of Thin Alumina Films on Steel.” Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society 69 (3): 239–49. https://doi.org/10.2298/JSC0403239L.

Luks, D. W. 1942. Vitreous high alumina porcelain, issued 1942. https://patents.google.com/patent/US2290107A/en.

Mazelsky, R, CS Duncan, RG Seidensticker, RA Johnson, JP Mchugh, HC Foust, and PA Piotrowski. 1974. “Multipurpose Electric Furnace System.[for Use in Apollo-Soyuz Test Program].” https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19760003136/downloads/19760003136.pdf.

Otani, Norio, Shinichi Ishimatsu, and Toshiaki Mochizuki. 2008. “Acute Group Poisoning by Titanium Dioxide: Inhalation Exposure May Cause Metal Fume Fever.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 26 (5): 608–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2007.08.018.

Raj, Rishi, and Kalvis Terauds. 2015. “Bubble Nucleation During Oxidation of SiC.” Edited by Avi Zangvil. Journal of the American Ceramic Society 98 (8): 2579–86. https://doi.org/10/f7k4b5.

Roth, Don J., Richard W. Rauser, Nathan S. Jacobson, Russell A. Wincheski, James L. Walker, and Laura A. Cosgriff. 2010. “NDE for Characterizing Oxidation Damage in Reinforced Carbon-Carbon.” In Ceramic Transactions Series, edited by Dileep Singh, Dongming Zhu, Yanchun Zhou, and Mrityunjay Singh, 167–80. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470909836.ch15.

“Sintering.” n.d. Accessed March 11, 2020. http://www.bap.mu.edu.tr/icerik/metalurji.mu.edu.tr/Sayfa/Kalemtas_A_Sintering_2014.pdf.

Teter, A. R. 1965. “EVALUATION OF BINDERS FOR MACHINABLE UNFIRED CERAMICS,” December, RFP–659, 4588054. https://doi.org/10.2172/4588054.

Wan, Wei, Chun-e Huang, Jian Yang, and Tai Qiu. 2014. “Study on Gelcasting of Fused Silica Glass Using Glutinous Rice Flour as Binder.” International Journal of Applied Glass Science 5 (4): 401–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijag.12060.